Complete immersion

How a single word is quietly drowning the events industry

We never agreed on the meaning of the word immersive, did we?

If we did, if there was ever a moment when it was defined such that it referred to something specific, quantifiable or testable, that meaning has been so thoroughly forgotten that it might as well have never been defined at all. Still, we continue to use it relentlessly, flooding our portfolios, agency creds, Instagram captions and award submissions with a word that could describe anything from a theatre production to a dinner party.

Immersive belongs to a litany of words, including bespoke, curated, and luxury, that have colonised event industry language. Each one promises specificity while delivering obscurity and suggests expertise, but the only barrier to using them is the courage needed to do so. These words are the primary culprits in the linguistic framework for an industry that’s learned to talk around what it actually does. Immersive ranks at the top of this list and is the most far-reaching and ambitious, yet committed to the least in practice.

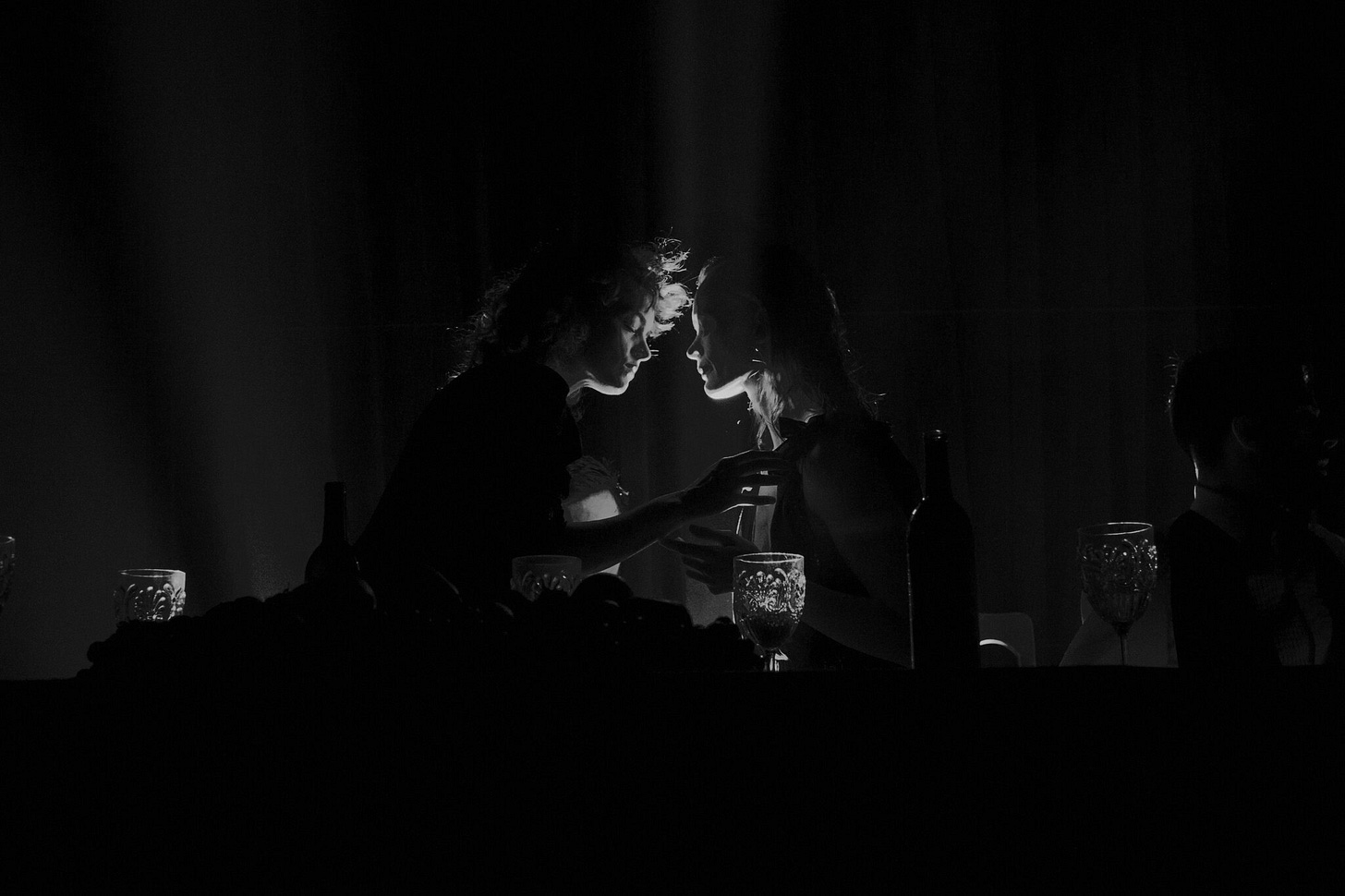

Immersive has become ubiquitous in our self-presentation. Portfolios boast of immersive celebrations without clarifying what actually makes them immersive. Instagram captions are written and deployed with the unwarranted confidence of people who’ve stopped questioning what the words they use mean, or even whether it matters at all if the accompanying visual is aesthetically pleasing or scroll-stopping enough. Case studies feature immersive in the opening sentence, doing the heavy lifting that being specific and just describing the work should do. Details can be assessed, judged, and found lacking, but immersive floats above critique and accountability, a cloud of implication that sounds impressive without saying anything at all.

Agencies and suppliers scramble to showcase their expertise in creating immersive experiences, and here the circular reasoning reaches its zenith. We claim expertise in immersive experiences because we create them, and we create them because we claim expertise. Nobody needs to define what immersive experiences are or demonstrate they have actually created one, because our expertise is self-evident from the fact that we’re claiming it.

This is the same reasoning that supports most luxury markets when you strip away the packaging. Luxury handbags are expensive because they’re luxury, and they’re luxury because they’re expensive.

Immersive is a disguise that signals sophistication while concealing nothing at all.

It’s a word that suggests vision and innovation, but only needs the user to believe, or pretend to believe, that they have understood its meaning.

Comfort in repetition

Scroll through your toxic social media platform of choice and count how many times immersive appears, then try to determine what the word is actually telling you in the context in which it’s being used.

You’ll find it attached to multi-million-pound productions involving a huge cast and crew operating in bespoke environments. You’ll also find it beneath pictures of a corporate Christmas party with a mirror ball and a photo booth. Both use the same word to describe wildly different endeavours. The word has become a badge of ambition, sophistication, and innovation that needs no proof. It implies value without having to demonstrate it.

The word serves as a creative shorthand for those unable to explain what they actually do. If you can’t describe your recent event in a way that makes it stand out in an extremely saturated market, say it’s immersive. If you’ve created something truly impressive but within the bounds of what could be called ‘a great party, say it’s immersive. If you’re charging exorbitant sums for your service and are struggling to explain what your client is paying for, it’s immersive. Problem solved, meaning avoided.

When you can describe anything as immersive, you don’t need to spell out what makes it special, what makes it yours, or what justifies paying for it beyond using language associated with perceived value itself. The word suggests vision or innovation while avoiding specifics, implying you’ve considered the ‘experience’ deeply without any real pressure to do so.

If it’s a word you’ve used, you might have noticed that every time you do, there’s a tiny flicker of hesitation, a moment of awareness where some part of you quietly observes, “I have no idea what I’m promising here.”

The same applies to bespoke (which should be a baseline expectation in service if not in material output), curated (which now refers to making choices, not deeper, thoughtful and intentional selection), and luxury (a pricing signal, not a quality marker).

The more something is described as bespoke, curated, luxury, or indeed immersive, the less we’re inclined to believe it.

The cost of ambiguity

Immersive has become a way to say we aren’t just organising parties or events. It implies we’re creating rich experiences, designing worlds and thinking beyond tangible elements like catering or floristry. The word elevates event management, read as mundane admin and logistics, into event or experience design, a superior craft where every detail serves a grand vision. But with everyone describing their work as immersive, the line of distinction is barely visible.

What makes this especially insidious is that the word’s vagueness offers an economic advantage. When clients describe their desire for something special or memorable, we might interpret this as a signal to pitch our ideas as immersive, allowing both parties to convey ambition without committing to specifics. If your work is immersive, you position yourself at a price point that justifies fees inflated by the creative effort involved, beyond mere coordination. The word enables everyone to operate in productive ambiguity. The client feels sophisticated for requesting it, you feel proud for providing it, and the silent pact of mutual delusion is complete. And because there’s no objective measure of immersion, there’s no accountability if the delivered output is little more than a very nice event.

This is why immersive just won’t go away, despite those of us who have recognised its emptiness. It’s surreptitiously used to signify which market tier you operate in without explaining what sets that tier apart or why you belong there, and its continued proliferation further accelerates its growth. When every event is captioned on Instagram as immersive, regardless of what is delivered, the word itself maintains its own illusion. Clients browse portfolios and agencies’ feeds where everything is described as immersive, and the word becomes the expectation of a certain standard of work.

What’s sad about it all is how much this inflation of language may have replaced, to some extent, genuine creative ambition. Why bother trying to create something immersive when you can just label it as such? Why risk experimentation when playing it safe earns the same terminology, Instagram engagement, and financial reward? Using the word immersive should push us towards having to create real immersion.

We’ve built an economic system where meaningless language is more profitable than meaningful work.

Algorithmic immersion

Attempts to restore the word’s meaning reveal everything we need to know. We bolt on modifiers like truly immersive, fully immersive or completely immersive, as if emphasis could repair what overuse destroyed. Or we build elaborate taxonomies, using tangential words like experiential or transformative, hoping they’ll bring clarity when, in these cases, they’re used to mean exactly the same thing. Each is just another way of circling around the void, proof that we’ve run out of language to describe what we actually do.

Then add AI into the mix, which industrialises the word’s inadequacy. LLMs trained on reams of events content, which is to say years of ambiguous, aspirational marketing copy, have learned that immersive is something we value, so they generate more of it. Now we’re deluged with LinkedIn slop promising immersive celebrations, Substack essays analysing immersive trends, and websites touting immersive event design. LLMs don’t understand what immersive means (join the club), they just recognise its regular use alongside other relevant terms and reproduce the pattern in a nightmarish, self-replicating loop of vagueness.

We’ve developed machines that can replicate our lack of understanding at an unprecedented scale, which would be impressive if it weren’t so damning.

The more AI-generated content reinforces words like immersive, the more we use them, and the more we train future models to do the same. This loop exposes our limitations more than the AI’s. If ChatGPT can write copy indistinguishable from your own, maybe the algorithm didn’t learn from you, maybe you learned from it.

Lost in translation

All this linguistic inflation leads to real professional consequences. I recently encountered a specific situation that might resonate. A potential client approached me after attending what they called an immersive event, saying they wanted the same. Upon further investigation, the event they described looked like a great party, but little more than that.

This made my job more difficult. I either had to meet their inflated expectations and deliver something immersive (even if they had mentally budgeted for something more straightforward) or gently recalibrate their understanding of the word without making them feel foolish for using it, and without insulting the event they referenced or underplaying my own abilities. That conversation, a delicate dance of diplomacy around a word that says everything and nothing, is time that could have been better spent.

If we can’t name what we’re doing, we lose entirely the ability to assess how well we’re doing it. We can call an event immersive if the environment is so complete, so all-encompassing, and the details so cohesive that disbelief is suspended and guests forget where they are. But the same goes for a planner who books a DJ and hires a photo booth. The word doesn’t guarantee any real delivery of its promise, particularly if everyone uses it regardless.

Every time we use immersive instead of something truer, we lose the opportunity for precision. Was it theatrical or intimate, participatory, multi-sensory, narrative-driven? Each of these words conveys something specific. Each sets an expectation and paints a picture. Because of its overuse, immersive says nothing more than that someone, somewhere, decided it was the word to use.

What is immersive?

It seems obvious, though rarely acknowledged, that immersion is a binary concept. Something is either immersive or it isn’t.

An event can’t be somewhat immersive any more than you can be somewhat pregnant or somewhat on fire.

The word describes a complete state. The condition of being so absorbed in an experience that you forget you were in one at all, where the constructed reality becomes, temporarily, reality itself.

So who or what is immersive? Punchdrunk is. You spend three hours wandering through a multi-storey building where every room is a detailed set, actors ignore your presence while performing scenes you have to discover, where you choose your own path and may see a completely different show from the person next to you. Secret Cinema is. You arrive in costume, inhabit a role, and the experience begins before you arrive, with the boundaries between audience and performance dissolved. You Me Bum Bum Train is. You’re alone, disorientated, unsure of what’s happening next, thrust into scenes in which you must participate and cannot opt out. These experiences, to some extent, all demand surrender, commitment, uncertainty, a bit of jeopardy and the feeling of forgetting that you’re at an event at all.

A brand event or private party, however stylish or ambitious, likely operates within different constraints and ultimately serves different purposes. A host wants to be celebrated. Guests want to socialise, connect, have conversations, eat, drink and leave when they choose. No one wants to forget they’re at a wedding or surrender control of what happens next. In these contexts, immersion is both unlikely and undesirable.

This doesn’t make them inherently lesser. An exquisitely designed event with theatrical elements, a cohesive aesthetic, and careful attention to guest experience is highly valuable and worth whatever the client pays. It doesn’t need to transport guests to another realm, to be immersive, to be excellent at what it is and justify its worth.

One of the many issues here is that if immersive now sits at the top of a false hierarchy, it implies that immersion is the highest goal an event can pursue. In reality, it’s one mode, among many, suitable for certain events and totally unsuitable for most others. We’ve borrowed a word that describes something rare and specific and applied it to events that succeed precisely because they don’t dissolve the boundary between reality and constructed experience.

This may have warped our thinking. Instead of improving how we design events and parties to reach their goals, we pursue thinking that fundamentally contradicts them. Successful celebrations rely on guests knowing exactly where they are, who they’re with and why they’re celebrating.

The most damaging aspect is how this de-skills us and prevents us from articulating the true value of our work. If we can’t call something “an exceptionally well-designed dinner party” without feeling it sounds inadequate, and instead describe it as an immersive experience to justify our output, creativity, or price, we’ve lost the ability to defend and promote the work we do. A dinner party, executed with skill, imagination, and precision, is immensely valuable on its own terms. Suggesting it’s something else entirely only diminishes it, and us.

Saying it like it is

If we’re able to abandon this hollow language, the result is almost always more compelling. “A theatrical dinner where actors guide guests through a narrative across multiple rooms” is far more persuasive and engaging than “an immersive dining experience”. The honest version is more effective. It’s specific, visual, credible, sets clear expectations, and justifies the fees charged for it.

We must choose words that retain meaning and that our younger selves, before years immersed (!) in client management taught us to speak in abstractions, would recognise as actual descriptions of actual output.

Immersive is corrosive as much as it is meaningless. It’s made us stop thinking clearly about what we create, why it matters, and, by extension, worse at doing it. It’s allowed us to hide behind weak vocabulary, sound ambitious without being ambitious, and charge premiums for work we can’t quite articulate the value of because we’ve stopped trying to articulate anything at all. We’ve let a single hollow word replace the difficult, necessary task of understanding what makes our work ours.

Deep down we know, and have always known, that what we do isn’t immersive.

The question is whether we’ll continue pretending it is or begin describing it truthfully, even if it sounds less impressive, even if we have to admit that we plan parties; exceptionally detailed, beautifully executed, valuable parties.